PHOTOS BY STEVE BRINKMAN

As the 1999 Aloha Festivals Celebration swirls around Big Island communities

with another month of traditional Hawaiian pageantry and cultural excitement,

we must pause and recognize some of the people who have helped to perpetuate

this unique culture in all its many facets. The following are excerpts

from a new book by M J Harden, called Voices plantation of Hawaiian culture

through the stories and personalities of twenty-four Hawaiians, each an

expert in a valued discipline or skill. Here,we have chosen to focus on

the stories of Big Island kupuna, nine of whom are interviewed in Harden’s

book. Here is a sample of some of the keepers of the Hawaiian flame.

Nona

Beamer: teacher, kumu hula

“Maybe

it’s like listening to that still small voice—that we have to have time

to know ourselves and think inwardly and not to be so concerned with every

day affairs that we forget this place in our hearts that’s peaceful and

loving and kind, and it just surmounts any problems and troubles we have

in our lives.”

“Maybe

it’s like listening to that still small voice—that we have to have time

to know ourselves and think inwardly and not to be so concerned with every

day affairs that we forget this place in our hearts that’s peaceful and

loving and kind, and it just surmounts any problems and troubles we have

in our lives.”

“Mana is life

force, the power that enables us to live. So many people go throughout

life without even using mana; they walk through life like they are in

a fog. With mana you perceive what life really means and what it’s saying

to you.”

“Mana is life

force, the power that enables us to live. So many people go throughout

life without even using mana; they walk through life like they are in

a fog. With mana you perceive what life really means and what it’s saying

to you.”

Herb Kane: Artist, historian

“What

intrigued me was to see, if by building this canoe (Höküle’a) and putting

it to active use and taking it out on a cruise throughout the Hawaiian

islands, introducing it to the Hawaiian people, training Hawaiians to

sail it, if this would not stimulate shock waves or ripple effect throughout

the culture—in music and dance and the crafts. And we know it did.”

“What

intrigued me was to see, if by building this canoe (Höküle’a) and putting

it to active use and taking it out on a cruise throughout the Hawaiian

islands, introducing it to the Hawaiian people, training Hawaiians to

sail it, if this would not stimulate shock waves or ripple effect throughout

the culture—in music and dance and the crafts. And we know it did.”

Elizabeth Lee: lau hala weaver

“I

can’t take it with me. To be honest with you, that’s why a lot of our

artwork has been lost. I remember way back, I can hear them saying: ‘I’m

going to teach you this thing, but don’t you teach someone else because

this is ours—our pattern, my pattern, my style of hat.’ And look what

we have today:

“I

can’t take it with me. To be honest with you, that’s why a lot of our

artwork has been lost. I remember way back, I can hear them saying: ‘I’m

going to teach you this thing, but don’t you teach someone else because

this is ours—our pattern, my pattern, my style of hat.’ And look what

we have today:

We have not much left.”

Margaret Machado: lomilomi massage master

“I

can go right through you and tell you just exactly where it is. When I

look at you I know all about you. You don’t have to tell me about yourself.

It’s written on your countenance. All your muscles and your bones reflect

your countenance, how you work with your body. When I look at you, I know

that all this is coming up from your hands and feet to your countenance.

It shows on your face. I look at your face, one side is tight. I look

at your brain, one side lacking oxygen. “They ask me, ‘How do you know?’

I say, ‘It’s there. I didn't do it. You did it. That’s your face, that’s

your body.’”

“I

can go right through you and tell you just exactly where it is. When I

look at you I know all about you. You don’t have to tell me about yourself.

It’s written on your countenance. All your muscles and your bones reflect

your countenance, how you work with your body. When I look at you, I know

that all this is coming up from your hands and feet to your countenance.

It shows on your face. I look at your face, one side is tight. I look

at your brain, one side lacking oxygen. “They ask me, ‘How do you know?’

I say, ‘It’s there. I didn't do it. You did it. That’s your face, that’s

your body.’”

George

Na’ope: kumu hula,

originator of Merrie Monarch festival

“The

hula is Hawai‘i. The hula is the history of our country. The hula is a

story itself if it’s done right. And the hula, to me, is the foundation

of life. It teaches us how to live, how to respect, how to share. The

hula, to me, is the ability to create one’s inner feelings and no one

else’s.”

“The

hula is Hawai‘i. The hula is the history of our country. The hula is a

story itself if it’s done right. And the hula, to me, is the foundation

of life. It teaches us how to live, how to respect, how to share. The

hula, to me, is the ability to create one’s inner feelings and no one

else’s.”

Pua

Van Dorpe: master kapa

cloth maker

“The

work was done almost exclusively by the women and that intrigues me. I

want the world to know what that Hawaiian woman did and what she went

through to produce the ultimate art piece in the fiber arts. When I work,

I feel like that Hawaiian woman, back in time.”

“The

work was done almost exclusively by the women and that intrigues me. I

want the world to know what that Hawaiian woman did and what she went

through to produce the ultimate art piece in the fiber arts. When I work,

I feel like that Hawaiian woman, back in time.”

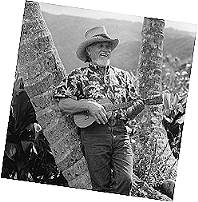

Clyde “Kindy” Sproat

“One ‘ukulele

and one soul can do a lot.”

Said by a man who means what he says and lives by his words, both spoken

and sung.

Clyde “Kindy” Halema‘uma‘u Sproat is Hawai‘i’s best at what he does—storytelling

and singing of old Hawaiian songs. His favorite melodies are songs from

the 1800s and early 1900s—songs rarely written down, just handed down

on back porches, songs that might be long gone except for the phenomenal

memory and committed zeal of Kindy Sproat.

It

is his mission and his love.

It

is his mission and his love.

“These are the songs I grew up with. They make me come alive. The tunes

haunt me,” he says. “Who knows them? Who sings them? Nobody.So, I feel

I should preserve them. They’re beautiful and they tell beautiful stories.

I don’t expect any of the young ones to sing and play the songs like I

do because they never heard them in their time. I’m just playing and singing

what I heard in my time. And I retained all that.”

Did he ever. By the time he was in first grade, he knew about 400 songs,

both Hawaiian and English. Now he has no idea how many he knows.

He sings because he loves to. For no other reason. When he’s alone, he’ll

sing out loud just to entertain himself. In the middle of a conversation

he’ll break into song. He’s been known to sit upright in bed with an old

tune suddenly remembered from his sleep.

He

never intended to make a living at it or to become famous for it.

He

never intended to make a living at it or to become famous for it.

“I don’t know about being famous,” he answers when asked how fame has

altered his life. “I’m just me, you know. Never changed one hair on my

head. I’m still the same.”

In 1988, the National Endowment for the Arts honored his importance to

Hawai‘i’s heritage by presenting him with a National Heritage Fellowship

Award, an honor given to America’s top folk artists.

His greatness lies not in his musicianship, as he readily admits: “I just

play basic keys. I’m a singer, I’m not a musician. I don’t know the first

thing about music or music theory. I don’t read notes. I just picked it

up.

“When you hear a song and you learn it and you know it, you take it down

and strain it through your heart. You just listen with your heart. Open

the ears of your heart and you can hear something good all the time.”

This attitude plus his talent have made him famous both in Hawai‘i and

on the Mainland. He didn’t seek this fame, but the organizer of national

folk festivals discovered him in Hawai‘i and kept pestering Sproat until

he agreed to attend an upcoming festival in Ohio.

“Joe

Wilson seemed like just an old hayseed with a pot belly and a worn-out

sleeve with a deep Southern accent. I didn’t know who he was. He’s the

head of the National Council for Traditional Arts in Washington D.C.,

and I just thought he was an old bean picker. He was a friendly guy.

“Joe

Wilson seemed like just an old hayseed with a pot belly and a worn-out

sleeve with a deep Southern accent. I didn’t know who he was. He’s the

head of the National Council for Traditional Arts in Washington D.C.,

and I just thought he was an old bean picker. He was a friendly guy.

“He said: ‘How’d you like to go to Ohio?’

“I said: ‘What for?’

“He said: ‘They have a national folk festival in Ohio and I want you to

go there.’

“I said: ‘Joe, I just built a cabin in the valley and the farthest I’m

going to go is to that cabin and back. I don’t want to go to Ohio.’“Every

day he kept bugging me. He said: ‘We need you to go to Ohio.’

“I said: ‘No, Joe, I don’t want to go anywhere.’

“We

got down to when he was going to get on the airplane (to return to the

Mainland) and he said: ‘You know, Kindy, you’re a stingy son of a bitch.’

“We

got down to when he was going to get on the airplane (to return to the

Mainland) and he said: ‘You know, Kindy, you’re a stingy son of a bitch.’

“I said: ‘Whoa, Joe, what’s all this about?’

“He said: ‘You know I’m a folklorist. I listen to

you and you’re one of the greatest in Hawai‘i, ![]() and

I’ve heard a lot of people, and you are great. You have so much to tell

the people but you’re a stingy son of a bitch and you don’t want to share

it.’ “I said: ‘Okay, Joe. You struck a chord there. What can I say?’ “Six

weeks later I was in Ohio.” He has now done these festivals for years.

Been all over the country and even played at Carnegie Hall. “What I love

is when you meet people,” he says characteristically. “I mean you don’t

know beans about them or their culture, but as soon as you strike a note

and start singing and playing, there is a bond. Music is a glue that bonds

people together.”

and

I’ve heard a lot of people, and you are great. You have so much to tell

the people but you’re a stingy son of a bitch and you don’t want to share

it.’ “I said: ‘Okay, Joe. You struck a chord there. What can I say?’ “Six

weeks later I was in Ohio.” He has now done these festivals for years.

Been all over the country and even played at Carnegie Hall. “What I love

is when you meet people,” he says characteristically. “I mean you don’t

know beans about them or their culture, but as soon as you strike a note

and start singing and playing, there is a bond. Music is a glue that bonds

people together.”

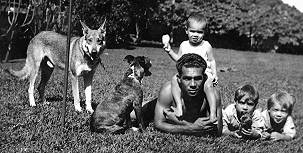

(above

photos)Kindy with Ukulele. At the homestead: Kindy (far right) with dad,

William, Bea (on shoulders) and brother Kamaka. Kindy and great-grandchildren.

Kindy gets a grooming from his little sis. Dad’s 80th birthday – l to

r: Kindy, Dale, William, Bea, Buzzy and Kamaka.

(above

photos)Kindy with Ukulele. At the homestead: Kindy (far right) with dad,

William, Bea (on shoulders) and brother Kamaka. Kindy and great-grandchildren.

Kindy gets a grooming from his little sis. Dad’s 80th birthday – l to

r: Kindy, Dale, William, Bea, Buzzy and Kamaka.

Marie McDonald

“Be

careful what you name your children,” the Hawaiians of old would admonish.

“They will live up to it, even when they don’t know.”

“Be

careful what you name your children,” the Hawaiians of old would admonish.

“They will live up to it, even when they don’t know.”

That is certainly the case with Marie Emelia Leilehua McDonald. As a child,

she didn’t know the story of her name and often wondered why she had such

an ordinary Hawaiian name as Leilehua, which refers to a common lei made

of flowers from the ‘öhia-lehua tree.

“There were so many people called Lei and so many called Lehua,” Mrs.

McDonald says, remembering how she complained to her mother about her

name. “Then I found out my name is not just a wreath of lehua blossoms.”

As

a young teenager she left Moloka‘i, where she was raised, to attend Honolulu’s

Kamehameha School, a school for native Hawaiian children. “Everybody there

had all these wonderful Hawaiian names,” she recalls. “So, when I went

home, I asked my mom: ‘Why did you give me this very commonplace name?’

When she told me the story, I felt so much bigger and better than all

those kids in Honolulu.

As

a young teenager she left Moloka‘i, where she was raised, to attend Honolulu’s

Kamehameha School, a school for native Hawaiian children. “Everybody there

had all these wonderful Hawaiian names,” she recalls. “So, when I went

home, I asked my mom: ‘Why did you give me this very commonplace name?’

When she told me the story, I felt so much bigger and better than all

those kids in Honolulu.

“She told me I was half of a set of twins and shortly after we were born,

my twin brother died. So my great-grandmother gave me this name, and the

meaning of it is ‘the strong child.’”

Years later, Leilehua took on an even more profound meaning for her when

a Hawaiian man she’d never met approached her as she was making a lei

during a park demonstration. He asked her in Hawaiian what her name was.

She just happened to be making a lehua lei at the time, and when she told

him her name, he responded prophetically: “Leilehua poetically means lei

expert.’“

Mrs. McDonald is, in fact, Hawai‘i’s foremost lei authority. She spent

seven years researching and writing her book, Ka Lei, published in 1978

and still the premier work on the subject. For her dedication to her art,

she received a National Heritage Fellowship Award in 1990 from the National

Endowment for the Arts, an award recognizing her contribution to Hawaiian

culture. Then, in 1992, she was named a “Living Hawaiian Treasure.”

“Just

living up to my name—that’s what I’m doing,” she says with a laugh, and,

as a matter of fact, the lei made of red lehua flowers is her favorite.

“My tutu (grandmother) knew what she was doing. She gave me the right

name.”

“Just

living up to my name—that’s what I’m doing,” she says with a laugh, and,

as a matter of fact, the lei made of red lehua flowers is her favorite.

“My tutu (grandmother) knew what she was doing. She gave me the right

name.”

Growing up in Hawai‘i, the lei “is there for every occasion,” Mrs. Mc-Donald

says. “It isn’t just a means of ornamenting the body. More important,

we make a lei and present it to honor our fellow man.”

In ancient times, the lei was ubiquitous. In her book, she writes: “It

appeared in the fields with the farmer when he invoked the blessing of

the gods upon his fields and crops; it was a necessary ornament for the

dancer; it was worn by the nursing mother; it was used in the healing

rites of the kahuna lapa‘au, the healing priest. It was the mark of chiefly

rank. It was offered to the gods. It was a symbol of love and lovemaking.

It belonged to the festivals and it brightened up the routine of daily

life as well. Children made them.

Men and women made them. Gods and goddesses favored them. The poets sang

their praises.”

The ancient Hawaiians made lei with whatever was available and so do good

lei makers today.

“I

do not resist using introduced materials,” Mrs. McDonald says. “I think

that is a sign of your creativity. I do consider lei making an art; I

don’t consider it some mundane ordinary thing, not the way we make lei.

If you are creative, you would use any introduced material, and that has

been our history.

“I

do not resist using introduced materials,” Mrs. McDonald says. “I think

that is a sign of your creativity. I do consider lei making an art; I

don’t consider it some mundane ordinary thing, not the way we make lei.

If you are creative, you would use any introduced material, and that has

been our history.

“When Hawaiians select materials for lei, first of all they select them

for fragrance, and, secondly, they select them for color, then movement.

The lei is used to ornament the dance. In the dance there’s movement,

so if you wear a lei that moves, it tends to attract attention. If it

laid still, you probably wouldn’t look at the expression on the dancer’s

face. But because it moves, it attracts you.”

People often ask her how to make a flower lei “last,” and she has a hard

time keeping herself from flippantly answering: “Bronze it.”

She explains: “It really bothers me because that’s not the reason for

the lei—that it should last forever. What should last is the thought,

the reason for giving that lei, the thought that went into it. Words can

be beautiful, but sometimes ‘I love you’ is not enough. If you say it

with something as beautiful as a lei, you know there’s a lot of power

in that.”

About

the Author:

Raised in the Midwest and living on Maui since 1984, MJ Harden has also

lived in Berkeley, San Francisco, Paris, Mexico, Nigeria and Washington,

DC After receiving a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University,

she traveled for sixteen years as a freelance travel writer until she

finally unpacked her bags on Maui. There, she published her own magazine

for residents, was editor of various medical and cultural magazines, and

wrote and published a Maui guidebook. Harden lives in Kula with her husband

and co-owns Hike Maui, the largest hiking company in the state. She describes

her decision to take on the monumental task of writing such a book as

“Voices”: “Fifteen years ago, when first visiting the Hana Museum, I saw

huge photos of ‘Faces of Hana’—mostly Hawaiian elders—and realized that

each of these faces had a fascinating story to tell. That’s when I first

thought that every Hawaiian generation should be chronicled, each detailing

the knowledge the kupuna still retained of the past, including how they

had added to the current, on-going culture during their own lives. “ The

idea of a book of interviews kept resurfacing over the years, but I kept

putting it off, frankly, thinking that someone else might do this somewhat

intimidating project. Interviewing the top Hawaiian elders would not be

an easy task. I thought perhaps a Hawaiian-born journalist might consider

doing it. However, various people kept mentioning that it was something

I should do because I like doing interviews, and apparently do them well,

and I have studied Hawaiian history, culture, botany and geology thoroughly.

Still, I kept thinking, no, let someone else do it. Then, an executive

editor of a large New York publishing company heard of the book and encouraged

me to write it. At that point, three years ago, I threw up my hands and

accepted that it was, in fact, my book to do. I would be the scribe to

take down this generation’s wisdom before they all left us.”

About

the Author:

Raised in the Midwest and living on Maui since 1984, MJ Harden has also

lived in Berkeley, San Francisco, Paris, Mexico, Nigeria and Washington,

DC After receiving a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University,

she traveled for sixteen years as a freelance travel writer until she

finally unpacked her bags on Maui. There, she published her own magazine

for residents, was editor of various medical and cultural magazines, and

wrote and published a Maui guidebook. Harden lives in Kula with her husband

and co-owns Hike Maui, the largest hiking company in the state. She describes

her decision to take on the monumental task of writing such a book as

“Voices”: “Fifteen years ago, when first visiting the Hana Museum, I saw

huge photos of ‘Faces of Hana’—mostly Hawaiian elders—and realized that

each of these faces had a fascinating story to tell. That’s when I first

thought that every Hawaiian generation should be chronicled, each detailing

the knowledge the kupuna still retained of the past, including how they

had added to the current, on-going culture during their own lives. “ The

idea of a book of interviews kept resurfacing over the years, but I kept

putting it off, frankly, thinking that someone else might do this somewhat

intimidating project. Interviewing the top Hawaiian elders would not be

an easy task. I thought perhaps a Hawaiian-born journalist might consider

doing it. However, various people kept mentioning that it was something

I should do because I like doing interviews, and apparently do them well,

and I have studied Hawaiian history, culture, botany and geology thoroughly.

Still, I kept thinking, no, let someone else do it. Then, an executive

editor of a large New York publishing company heard of the book and encouraged

me to write it. At that point, three years ago, I threw up my hands and

accepted that it was, in fact, my book to do. I would be the scribe to

take down this generation’s wisdom before they all left us.”